Advances in Delaying T1D Progression

Type 1 diabetes (T1D) is increasingly being treated as a condition requiring early intervention to slow progression, with numerous agents under investigation. The first disease-modifying drug—the Fc receptor-nonbinding anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody teplizumab—was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2022. Teplizumab is approved for the delay of the onset of clinical T1D in patients 8 years of age and older with stage 2 T1D, and is administered as a 14-day outpatient course delivered intravenously with dosing based on body surface area.1

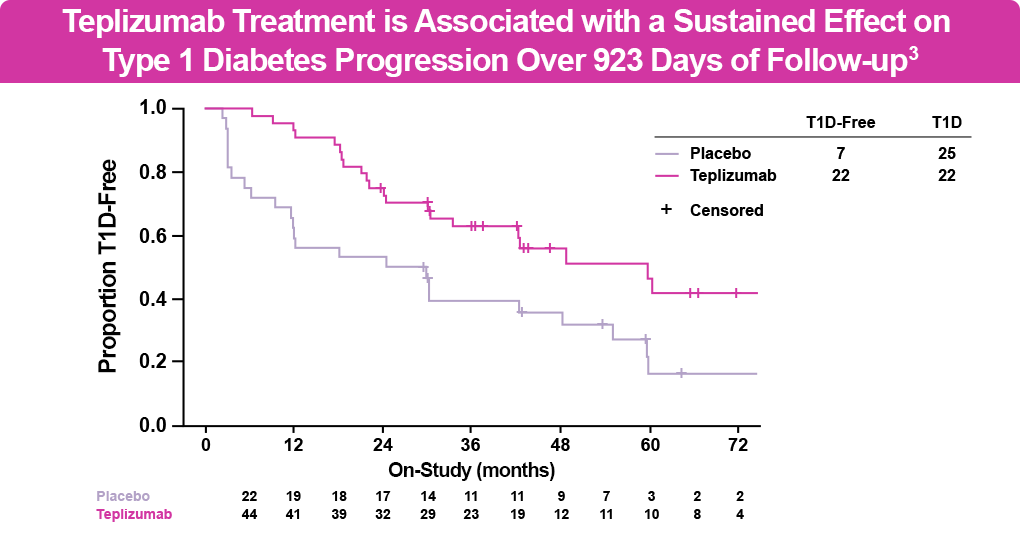

The FDA approved teplizumab based on the phase 2 double-blind AT-Risk (TN-10) clinical study of relatives of patients with T1D at high risk for developing clinical disease. In this study, patients received a 14-day course of teplizumab or placebo, with monitoring for progression every 4 months using an oral glucose tolerance test. At 6 years of follow-up, 50% of patients receiving teplizumab were diabetes free vs 22% of those receiving placebo (see figure below). The most common adverse events were rash and transient lymphopenia.2,3 Treatment with teplizumab delayed progression to stage 3 T1D by 32.5 additional months compared with placebo. The median time to diagnosis with teplizumab was 59.6 months vs 27.1 months with placebo, with certain individuals having even longer delays with teplizumab. Additionally, treatment with teplizumab was associated with reversal of C-peptide decline and improved beta cell function compared with placebo.3

In addition, results from the phase 3 PROTECT study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in late 2023, demonstrated the potential utility of teplizumab in newly diagnosed T1D.4

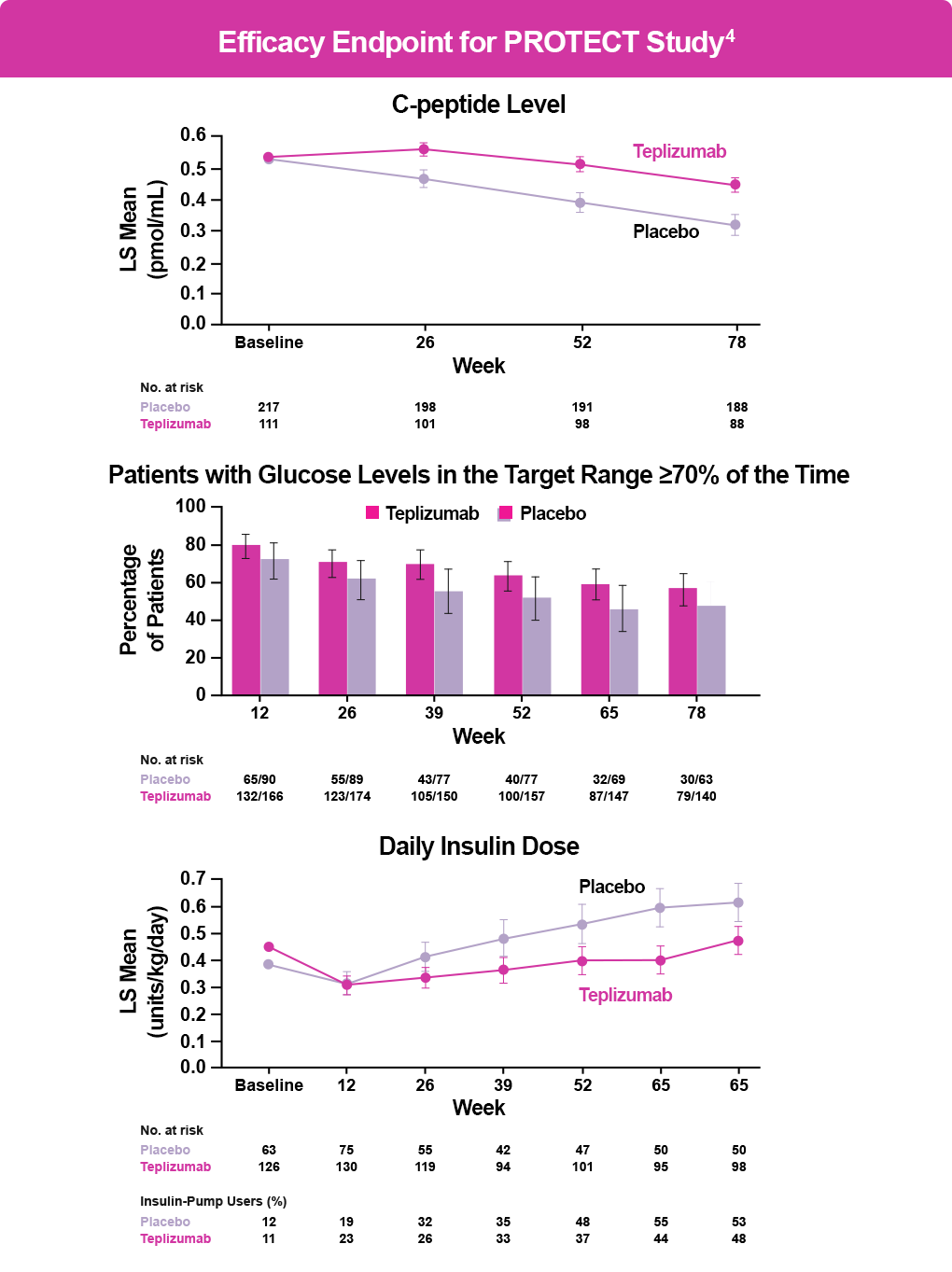

The PROTECT trial enrolled 328 children and adolescents with stage 3 T1D who had been diagnosed within 6 weeks of randomization and assigned them to receive either teplizumab or placebo for two 12-day courses. The primary endpoint was β-cell preservation as measured by stimulated C-peptide levels at Week 78. Key secondary endpoints were insulin doses required to meet glycemic goals, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C) levels, time in the target glucose range, and clinically important hypoglycemic events.4

Patients treated with teplizumab (n=217) had significantly higher stimulated C-peptide levels than patients receiving placebo (n=111) at Week 78 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.09–0.17; P < .001); 94.9% of patients treated with teplizumab maintained a clinically meaningful peak C-peptide level of ≥0.2 mmol/mL (95% CI, 89.5–97.6) compared with 79.2% of those receiving placebo (95% CI, 67.7–87.4) (see figure below). The groups did not differ significantly in the key secondary endpoints. Adverse events occurred primarily during drug or placebo administration and included headache, gastrointestinal symptoms, rash, lymphopenia, and mild cytokine release syndrome (CRS).4

Considerations for Teplizumab Use and Patient Selection

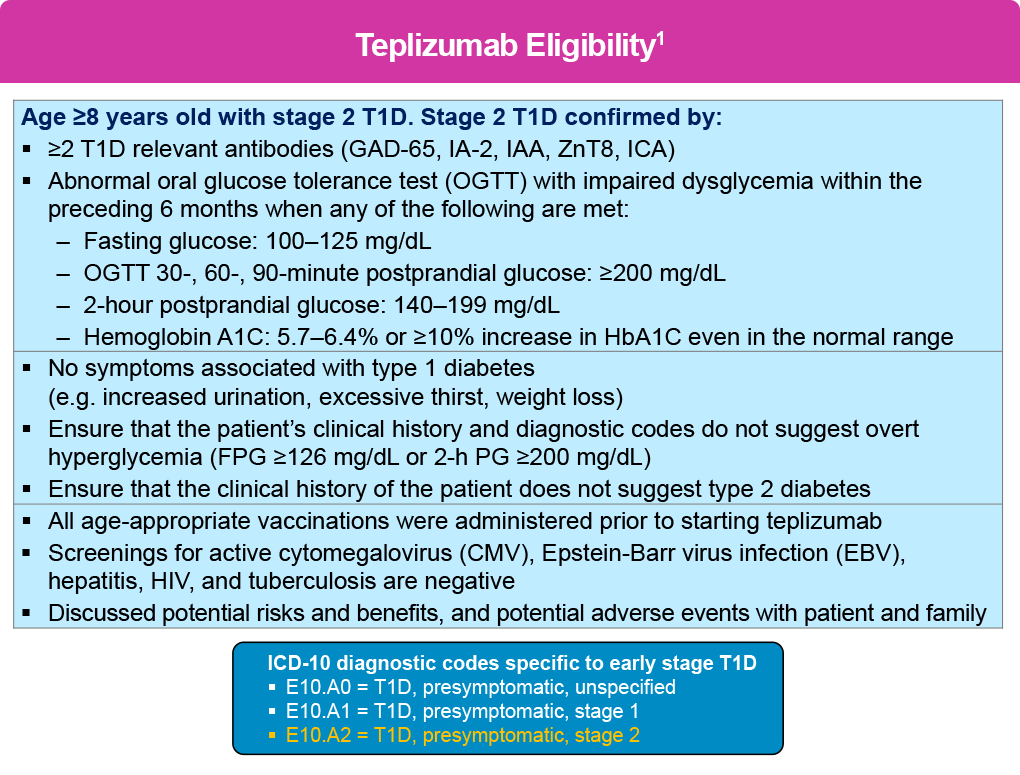

If an individual is confirmed to have stage 2 T1D, and upon appropriate education and shared decision-making about treatment goals with patients and their caregivers, clinicians should consider starting teplizumab to delay progression to stage 3 T1D, or refer eligible patients to specialty care based on the criteria shown below .1 In addition, diagnostic codes that are specific to early stage T1D were introduced in October 2024 that may facilitate patient selection.

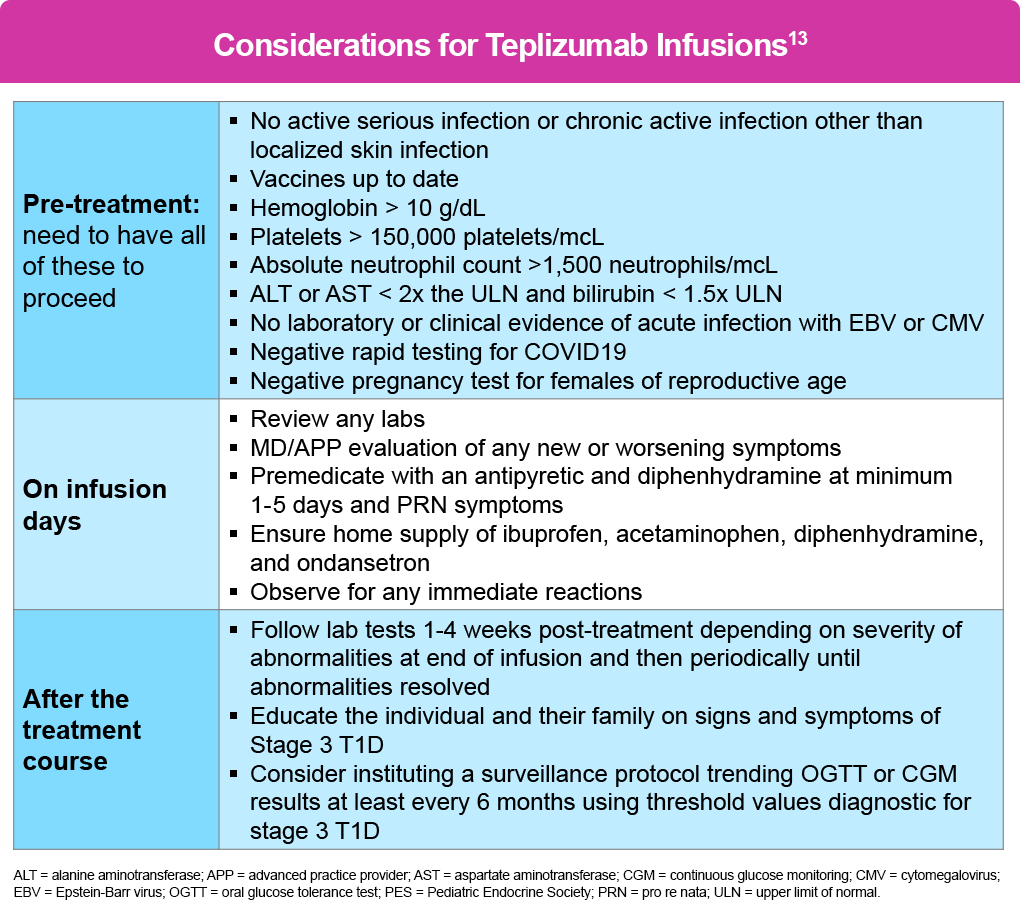

Teplizumab treatment requires careful patient selection and systematic implementation in dedicated infusion facilities with specially trained staff 13

The medication is indicated for patients aged 8 years and older with stage 2 T1D. Before initiating treatment, patients must complete all vaccinations and undergo screening for active infections, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and tuberculosis (TB). Baseline laboratory parameters required include adequate hemoglobin, platelets, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and liver function.13

There are no data on the use of teplizumab during pregnancy; thus, its use is not recommended for more than 30 days prior to planned pregnancy or during pregnancy. Individuals of reproductive age should also have a negative pregnancy test prior to administration.13

The treatment consists of 14 consecutive daily intravenous (IV) infusions (either via peripheral or central venous access) with an escalating dose schedule, beginning at 65 μg/m² on Day 1 and increasing to a maintenance dose of 1,030 μg/m² by Day 5. The protocol escalates the dose over the first 5 days because cytokine release syndrome (CRS) is most common early; but it can largely be prevented by pretreatment with an antipyretic and antihistamine given at least 30 minutes before infusion (max dose/age).

Each infusion runs over 30 minutes with a 1-hour observation period. The entire session should be about 2 hours, which allows for premedication. The patient may repeat pre-medications every 8 hours as needed, as well as ibuprofen/acetaminophen. A short course of glucocorticoids may be used to mitigate signs and symptoms of severe adverse reactions and moderate- to- severe CRS.13

Vital signs and symptoms should be monitored during treatment, with a particular emphasis on CRS, lymphopenia (typically reaching nadir around Days 4 to- 5 ), liver function abnormalities, and hypersensitivity reactions. Fever is the seminal sign of CRS. Specific criteria for holding or discontinuing treatment include CRS lasting more than 2 days, persistent severe lymphopenia or neutropenia, significant transaminitis (>5 times normal levels), active infection, or severe hypersensitivity reactions.13

Post-treatment management involves monitoring for progression to stage 3 T1D every 6 months, typically through OGTT or continuous glucose monitoring.13 A summary of these recommendations is shown in the table below, which are part of the 2024 Pediatric Endocrine Society (PES) guidance on teplizumab treatment.13

Teplizumab is also being investigated in the phase 4 PETITE-T1D trial in patients <8 years of age with stage 2 T1D (NCT05757713) and was also investigated in a phase 2 extension (NCT04270942) of the AT-Risk (TN-10) trial.

Other Emerging Disease-Modifying Therapies for T1D

Several other investigational agents are in development. To date, most have been tested in new-onset T1D, some with mixed results; additional studies are ongoing. These studies include additional approaches to modulating or depleting effector T cells, decreasing B cells and antigen presentation, as well as anti-inflammatory and beta cell protective agents. Some of the key investigational agents are discussed below.

Rituximab. This anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody targets B-lymphocytes and is approved for the treatment of several oncologic and autoimmune conditions. In the Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Anti-CD20 Study, rituximab infusion at Week 0, 1, 2, and 3 after T1D diagnosis delayed beta-cell function decline at 12 and 24 months, reduced HbA1C levels over 12 months, and led to less need for insulin. However, no difference was shown after 30 months with rituximab. Primary adverse events occurred with infusion, with no increased rate of neutropenia or infection.6 it is currently being studied in combination with abatacept in the T1D RELAY trial.14

Imatinib. This tyrosine kinase inhibitor approved for the treatment of chronic leukemia was assessed in a phase 1 trial in 67 adult patients with recent onset T1D. Results suggested some benefit on beta-cell function up to 12 months, which faded by 24 months. Infection and infestation and gastrointestinal adverse events were more common in the imatinib group.7

Abatacept. This CTLA4-Ig is approved for use in psoriatic arthritis and other autoimmune conditions. A study in 112 participants (age 6–36 years) with recently diagnosed T1D demonstrated beta-cell preservation in the intervention group at 2 years and an estimated 9.6-month delay in decline of beta-cell function throughout the study. There was no increase in infections or neutropenia.8 Abatacept is also under investigation as a preventive therapy in at-risk children and adults.9

Verapamil. This antihypertensive medication downregulates a thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), the overexpression of which induces beta-cell apoptosis. A double-blind randomized clinical trial in 88 children and adolescents aged 7 to 17 years with newly diagnosed T1D found greater B-cell preservation at 1 year in the verapamil group vs placebo, as well as a slightly lower HbA1C.10 It is also being investigated in adults newly diagnosed with T1D for beta-cell preservation.9

Golimumab. This human monoclonal antibody specific for tumor necrosis factor-alpha is approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis, and other autoimmune conditions in pediatric and adult settings. A phase 2 study found higher C-peptide levels and less insulin use in children and young adults with T1D receiving golimumab versus placebo, with 43% of those in the golimumab group achieving a partial remission. There were no significant differences in safety between the 2 groups other than a slightly higher rate of mild infections with golimumab.11 A phase 1 trial evaluated golimumab in children, adolescents, and young adults with at least 2 IAb+.15

Antithymocyte globulin (ATG). This antirejection drug depletes T cells through apoptosis, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, and complement-dependent cytotoxicity. A clinical trial in 89 people with T1D randomized to ATG alone, ATG with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (GCSF), or placebo demonstrated significant beta-cell preservation in those treated with ATG alone vs placebo but not in the ATG/GCSF group vs placebo. However, both ATG groups demonstrated HbA1C reductions at 2 years. Immune reactions were higher in the treatment groups but there were no differences in infection, neoplasm, or lymphatic cancers.12 Low-dose ATG is currently being investigated for delaying or preventing T1D in individuals aged 12 to 35 years with a 50% risk of clinical diagnosis of T1D within 2 years.9

Ustekinumab. This interleukin (IL) antagonist binds to the shared p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, targeting development of TH1 and TH17 cells implicated in the pathogenesis of T1D. A phase 2 study in 72 adolescents with recent-onset T1D found that at 12 months of treatment, C-peptide levels were 49% higher in patients receiving ustekinumab compared to those on placebo. The treatment was well tolerated with no increase in adverse events.16 The drug is currently under investigation in a phase 2/3 trial in adults with new-onset T1D.17

References

- Teplizumab (Tzield®) Prescribing information 2023. Provention Bio. https://products.sanofi.us/tzield/tzield.pdf.

- Herold KC, Bundy BN, Long SA, et al. An anti-CD3 antibody, teplizumab, in relatives at risk for type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:603-613.

- Sims EK, Bundy BN, Stier K, et al. Teplizumab improves and stabilizes beta cell function in antibody-positive high-risk individuals. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13:eabc8980.

- Ramos EL, Dayan CM, Chatenoud L, et al. Teplizumab and β-cell function in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2151-2161.

- Aronson R, Gottlieb PA, Christiansen JS, et al. Low-dose otelixizumab anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody DEFEND-1 study: results of the randomized phase III study in recent-onset human type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2746-2754.

- Pescovitz MD, Greenbaum CJ, Krause-Steinrauf H, et al. Rituximab, B-lymphocyte depletion, and preservation of beta-cell function. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2143-2152.

- Gitelman SE, Bundy BN, Ferrannini E, et al. Imatinib therapy for patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:502-514.

- Orban T, Bundy B, Becker DJ, et al. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:412-419.

- Min T, Bain SC. Emerging drugs for the treatment of type 1 diabetes mellitus: a review of phase 2 clinical trials. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2023;28:1-15.

- Forlenza GP, McVean J, Beck RW, et al. Effect of verapamil on pancreatic beta cell function in newly diagnosed pediatric type 1 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2023;329:990-999.

- Quattrin T, Haller MJ, Steck AK, et al. Golimumab and beta-cell function in youth with new-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2007-2017.

- Haller MJ, Schatz DA, Skyler JS, et al. Low-dose anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) preserves β-cell function and improves HbA1c in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1917-1925.

- Mehta S, Ryabets-Lienhard A, Patel N, et al. Pediatric Endocrine Society statement on considerations for use of teplizumab (Tzield™) in clinical practice. Horm Res Paediatr. 2024 https://doi.org/10.1159/000538775

- Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet. Rituximab-pvvr/Abatacept Newly Diagnosed Study (T1D RELAY). https://www.trialnet.org/our-research/newly-diagnosed-t1d/t1d-relay

- A Study to Evaluate SIMPONI (Golimumab) Therapy in Children, Adolescents and Young Adults With Pre-Symptomatic Type 1 Diabetes. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03298542#study-record-dates

- Tatovic D, Marwaha A, Taylor P, et al. Ustekinumab for type 1 diabetes in adolescents: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2024;30:2657-2666.

- Clinical Phase II/III Trial of Ustekinumab to Treat Type 1 Diabetes (UST1D2) (UST1D2). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03941132?cond=type%201%20diabetes&intr=Ustekinumab&rank=2