Early Screening and Detection

Given the increased understanding of the benefits of very early treatment for those with type 1 diabetes (T1D) including potentially preventive therapies, screening for T1D is now an important component of disease management.1 The need for early screening has only been heightened by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of teplizumab, the first drug shown to delay the onset of stage 3 T1D.2

Screening has several benefits, including the ability to3:

Reduce the trauma of an acute diagnosis for patients and families

Lower the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) at diagnosis in children with a genetic risk of T1D, who are then closely followed. Earlier identification can reduce the rate of DKA from 30% to 60% among patients who do not undergo early screening to less than 5% in screened populations.4 This is particularly important given that DKA at the onset of T1D is associated with increased mortality risk, longer hospitalizations, higher insulin requirements, shorter remission period, and worse glycemic control over time.3

Encourage caregivers to be more cognizant of clinical symptoms indicating T1D onset, leading to faster follow-up with healthcare providers

Provide time for patients and caregivers to learn about T1D and the lifestyle modifications required before clinical disease manifests

Identify patients for preventive therapies

Identify patients who may be eligible for clinical trials

Several large studies show that population-wide screening, including screening for genetic risk factors among newborns, is feasible and effective.5

As stated previously, the development of islet autoantibodies precedes the symptoms and clinical diagnosis of T1D by months or even years, and this subclinical stage is what makes screening possible. Several islet autoantibodies have been described, but only a select few have been incorporated into screening.6 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) currently recommends screening for presymptomatic T1D with a blood test to measure 4 major T1D-associated islet autoantibodies (IAbs): insulin (IAA), glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 (GAD65), insulinoma-associated antigen-2 (IA-2), and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8).6

The ADA also recommends standardized IA tests for adults with diabetes who have phenotypic risk factors that overlap with those for T1D (eg, younger age at diagnosis, unintentional weight loss, ketoacidosis, or short time to insulin treatment).6 Screening for individuals of all ages who have a history of autoimmune diseases and/or a family history of these conditions should also be considered. Most common autoimmune conditions associated with T1D risk are celiac disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and Graves disease, but other autoimmune conditions should also be taken into account.6

Patients with multiple islet autoantibodies should be referred to a specialized center for further evaluation, including consideration for a clinical trial or approved therapy to potentially delay the development of clinical diabetes.6

Most US-based guidelines recommend screening of individuals with a family history of these conditions or in the context of a research setting; however, considerations for screening in the general population are now being taken into account. For example, the guidelines from the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes (ISPAD) call for general population and targeted screening, noting that screening children between ages 2 and 6 years may provide the optimal sensitivity. It is not clear how often screening should be done in high-risk children or when and how to screen in adults.7

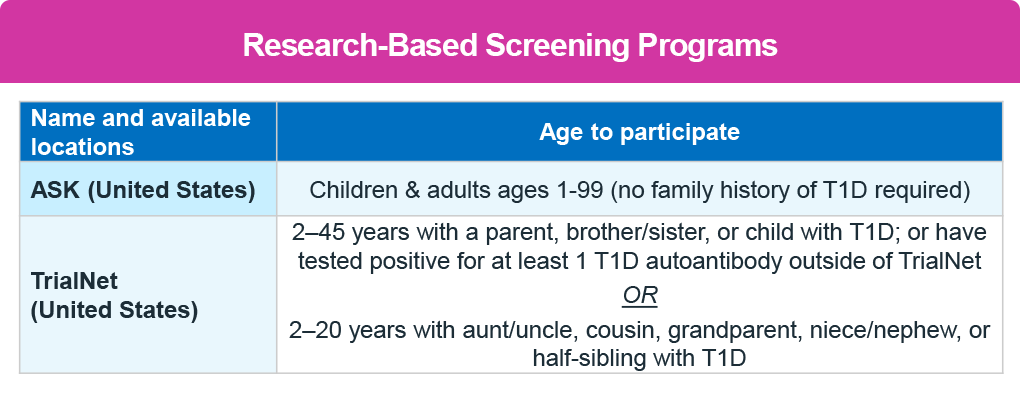

Several screening programs are available at local and national levels. TrialNet is a national registry that provides in-home test kits and reports results in patient-friendly language, highlighting the implications.

TrialNet

This research-based screening and clinical trial program is available for individuals who have a higher risk of developing T1D based on family history or previous autoantibody testing. Eligible individuals include those:

- Between 2.5 and 45 years old who have a first-degree relative with T1D

- Between 2.5 and 20 years old who have a second-degree relative with T1D

- Between 2.5 and 45 years old who have tested positive for ≥1 T1D-related autoantibody outside of TrialNet8

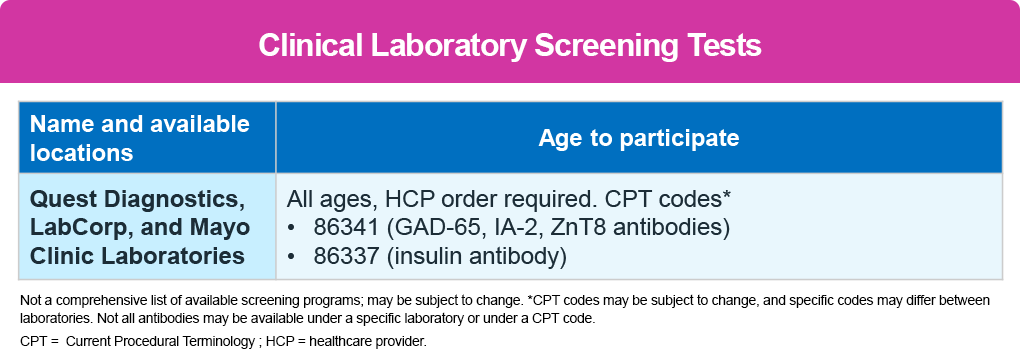

In addition, several other local screening programs are available, including ASK, PLEDGE, and CASCADE see table below. 9-11 No healthcare provider referral is needed. Screening is also available through clinical laboratories, which require a healthcare provider referral. The second table below also lists the laboratories and the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes to use. 12,13

More information can be found under the Reading & Resources section.

Interpreting Screening Protocols

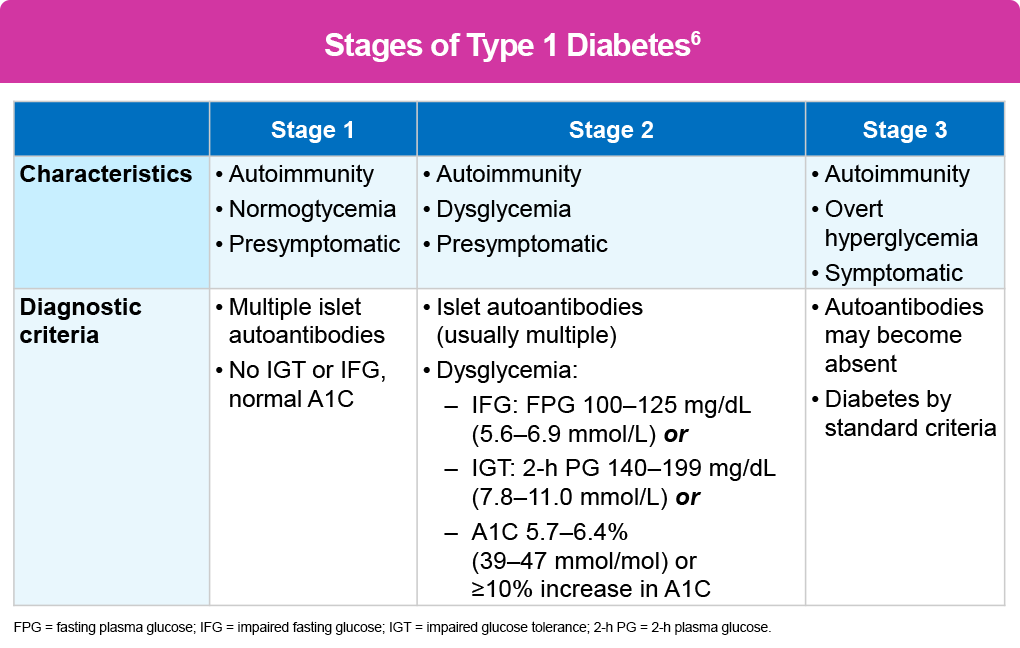

As the table below shows, the results of the screening test determine an individual’s stage of diabetes.

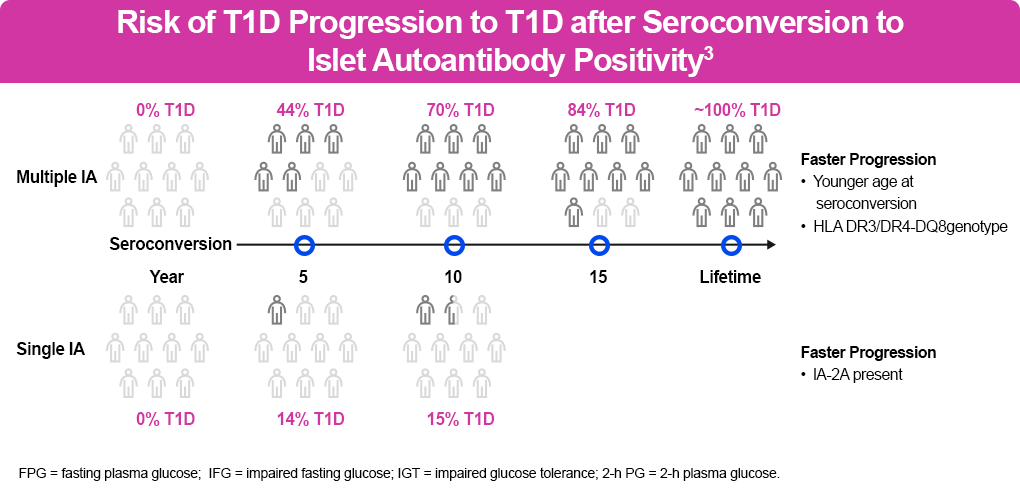

Pooled data from prospective studies among children with multiple IAs identified an aggregate risk of progression to diabetes after 10 years of 69.7% (95% confidence interval [CI], 65.1–74.3) in children with a single IA compared with 0.4% in children with no IAs (95% CI, 0.2–0.6).14 The figure below shows the risk of clinical progression based on screening findings.

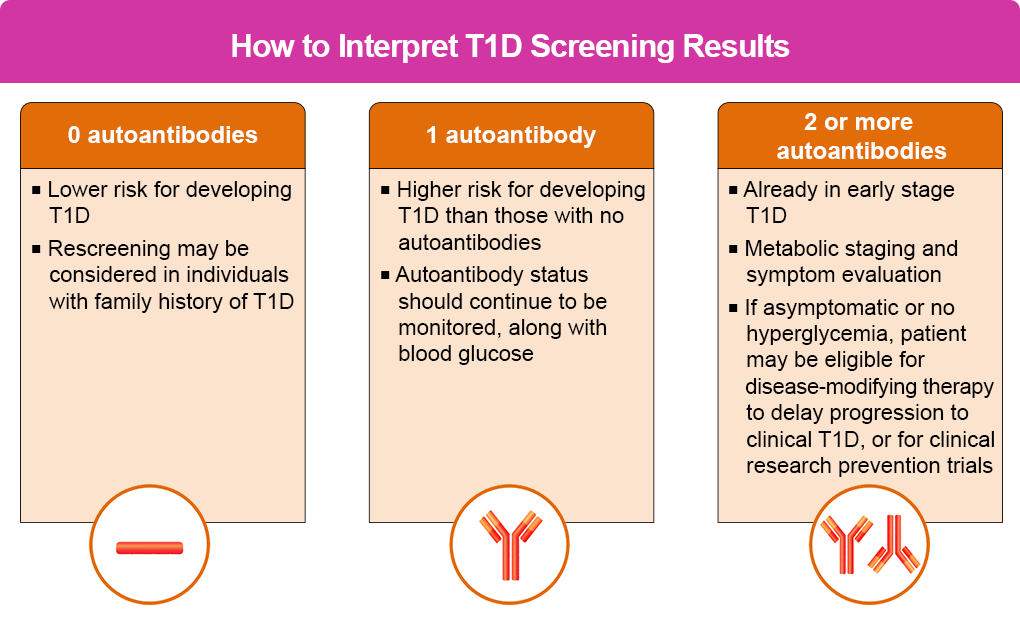

A negative test means the person has a lower risk of developing T1D, while those with ≥2 autoantibodies have a significantly higher risk so should be monitored.

More specifically:

- Children with a genetic risk of T1D in stage 1 with ≥2 autoantibodies, normoglycemia, and no symptoms have a 5-year risk of 44% of progressing to stage 3, a 10-year risk of 70%, and a lifetime risk of 100%.

- The risk for those in stage 2 with ≥2 autoantibodies and glucose intolerance or dysglycemia but no symptoms is 75% at 5 years and 100% over their lifetime.1,14

Screening Limitations

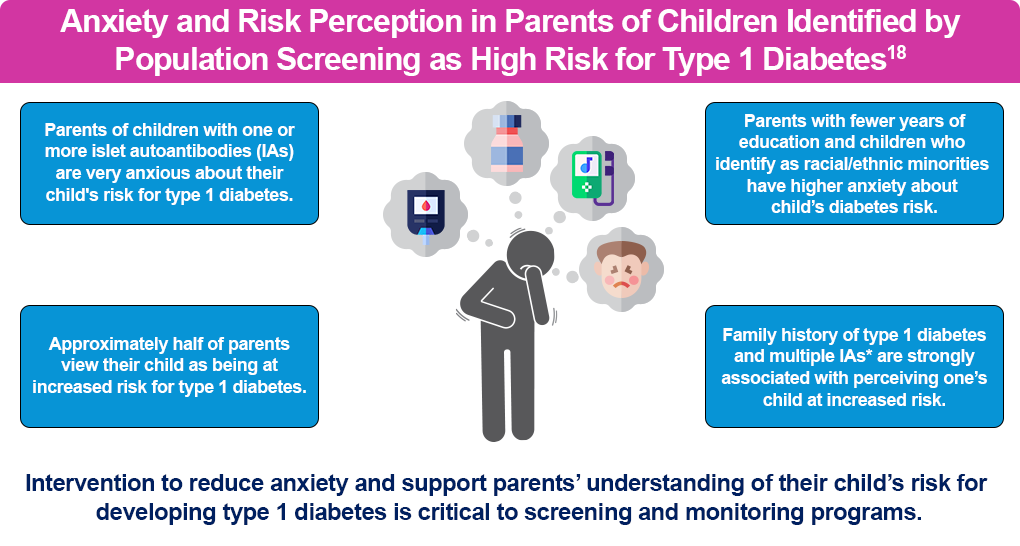

Screening does have limitations. It cannot provide a definitive timeline to diagnosis. In addition, the results may cause increased anxiety and psychological distress in patients and families, although this can be addressed with education and counseling.15,16

There are also patient and family barriers, including transportation, fear, concern about a negative psychological effect based on the findings, and a lack of knowledge about the benefits of screening. Clinical barriers include clinician knowledge of screening and a reluctance to offer screening, given the distress it may cause patients and their families.17

Educating Patients About Screening

Overcoming barriers to screening requires improved education for medical students and residents on the benefits of early screening and education for primary care physicians and endocrinologists on counseling patients and their families on the benefits of screening.

It is important that clinicians educate families about the importance of screening, using a shared decision-making model.

Clinicians have an important role to play in overcoming patient/family reluctance to screening. Here are some suggestions18:

- When asked about screening:

- Explain that the risk for developing T1D is greater for individuals who have a relative with T1D compared with people who do not have a relative with T1D

- Discuss the benefits and risks of testing, including the availability of an FDA-approved agent to slow disease progression

- Highlight the significantly reduced risk of DKA with screening and the short- and long-term implications of preventing DKA

- Stress the benefits of monitoring the disease before symptoms appear

- Discuss the potential to participate in clinical trials

- Remember that free expert information, assurance of privacy, testing for antibodies, and ongoing monitoring or enrollment in trials are available through the National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded research network TrialNet.

- When a positive test is confirmed outside of TrialNet or other research study:

- Discuss the results and implications

- Explain signs and symptoms of diabetes

- Develop a plan for further evaluation of risk and disease progression, and refer to TrialNet for expert advice

- Provide resources for emotional support, as appropriate

- Discuss the possibility of therapies that may impact progression of the disease.

- Refer to TrialNet or specialty care for expert advice about available options, as well as the risks and benefits of therapies for the individual

Monitoring After IAb+ Test19,20

Monitoring after a positive islet autoantibody (IAb) test is critical. The first positive test should be confirmed with a second within 3 months, ideally in a laboratory that meets the performance standards set by the Islet Autoantibody Standardization Program (IASP). The established gold standard to classify the stages of T1D is an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), but if it isn’t available, a 2-hour postprandial capillary blood glucose after a carbohydrate-rich meal to assess for dysglycemia will suffice.

Longer-term monitoring tools include self-monitored blood glucose (SMBG), periodic continuous glucose monitoring (CGM), a standard OGTT, random venous glucose, hemoglobin (Hb) A1C, and repeat islet autoantibody monitoring. Serial stimulated C-peptide measurement during an OGTT can be used to assess deterioration of beta cell function and predict risk development of T1D, which could highlight individuals who might benefit from therapies to prolong insulin secretion.19

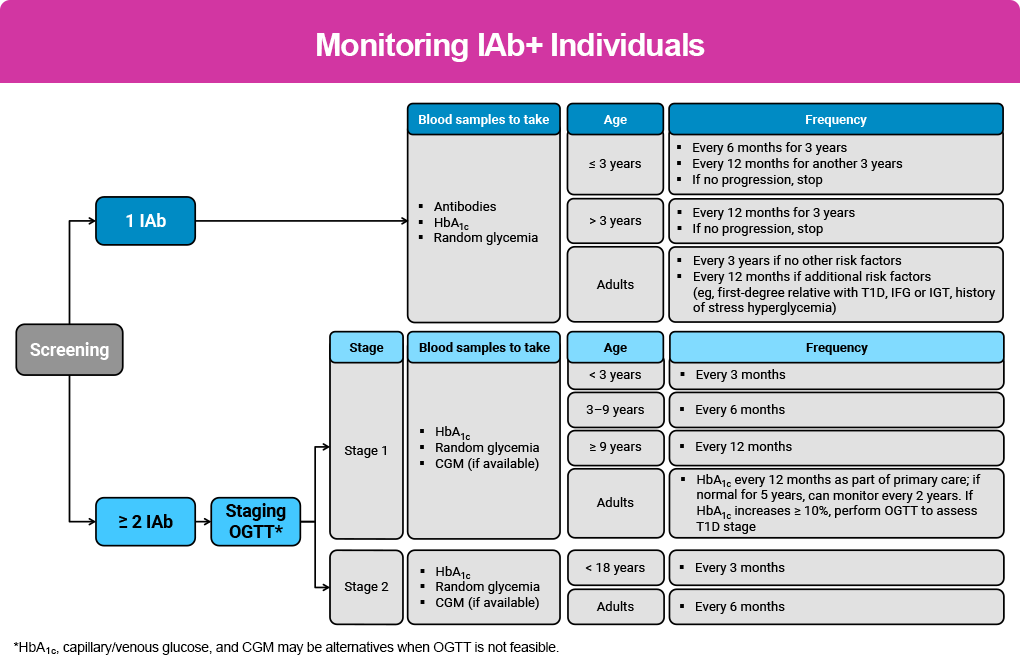

The primary care setting provides a good option for monitoring, particularly for those in stage 1, with no need for referral until clinically appropriate.19 More specific monitoring recommendations are below and in the Monitoring IAb+ Individuals figure, as well as in the Reading & Resources section.

Monitoring Children With Single IAb+19

- Confirm persistent single IAb+ status and negative status for other autoantibodies after first detection in a second sample, preferably in a laboratory that meets IASP standards using 2 independent methods.

- Monitor IAb+ status in children aged <3 years every 6 months for 3 years, then annually for 3 more years. Metabolic monitoring should include random venous or capillary blood glucose and HbA1C values at the same frequency. If no progression, stop autoantibody and metabolic monitoring and counsel for risk of clinical disease.

- Monitor IAb+ status annually for 3 years in children aged ≥3 years at first positive test. If no progression after 3 years, stop autoantibody and metabolic monitoring and counsel for risk of clinical disease.

- Provide education emphasizing potential symptoms and awareness of T1D to the families of children who revert to seronegative during autoantibody monitoring, or who do not progress.

Monitoring Children With Multiple IAb+19

- Confirm persistent multiple IAb+ status after first detection in a second sample, preferably in a laboratory that meets IASP standards using 2 independent methods.

- Measure HbA1C and venous or capillary blood glucose in children with stage 1 T1D once every 3 months for those <3 years old; at least every 6 months for children 3 to 9 years old; and at least every 12 months for children >9 years old.

- A 10- to14-day CGM can be used periodically to monitor glucose metabolism at a similar frequency as HbA1C measurement.

Longitudinal change in HbA1C of ≥10% from date of confirmed islet autoantibodies may indicate dysglycemia and disease progression, requiring an OGTT to assess T1D stage.

Individuals with confirmed stage 2 T1D should be followed by a specialist.

Monitoring Adults

Monitoring Adults With Single IAb+19

- Confirm persistent single IAb+ status after first detection in a second sample, preferably in a laboratory that meets IASP standards using 2 independent methods.

- Consider annual metabolic monitoring if there are additional risk factors, including first-degree relative with T1D, elevated genetic risk, dysglycemia, or history of stress hyperglycemia.

- No T1D monitoring is required for those with transient single islet autoantibody positivity who revert to being seronegative. Screening for diabetes in this group of adults should then follow standard of care guidelines for type 2 diabetes.

Monitoring Adults With Multiple IAb+19

- Confirm persistent multiple IAb+ status after first detection in a second sample, following the “rule of twos” and preferably using 2 independent methods. If a 2-test confirmation is not possible, a single blood test positive for multiple islet autoantibody status identifies a person with sufficient risk for metabolic monitoring.

- Provide all multiple IAb+ adults with SMBG meters and strips to use during illness or if symptoms are present.

- Monitor glycemic status in adults with stage 1 T1D and normoglycemia using HbA1C every 12 months as part of routine primary care visits.

- Metabolic monitoring every 2 years may be sufficient if normoglycemia extends to 5 years.

Monitoring Adults With Confirmed Stage 2 T1D19

- Monitor metabolic status using HbA1C every 6 months together with 1 of the following: blinded CGM (applied and interpreted by a trained healthcare professional); higher frequency of SMBG; or 2-hour plasma glucose following 75 g OGTT.

- Longitudinal change in HbA1C of ≥10% from date of confirmed islet autoantibodies may indicate dysglycemia and disease progression and requires an OGTT to assess T1D stage in order to determine eligibility for therapy.

- Consider C-peptide monitoring if dysglycemia or hyperglycemia occurs where the diagnosis of T1D or T2D is unclear. A C-peptide level of ≤0.20 nmol/l with IAb+ may be associated with T1D rather than T2D, but it is not absolute and many adults presenting with T1D have C-peptide above this level. C-peptide levels can also be falsely low in hypoglycemia (<70 mg/dL), after fasting, or in severe chronic hyperglycemia or DKA.

The figure below highlights current recommendations for monitoring IAb+ individuals.

Education and Psychosocial Support During Monitoring19,20

Individuals with IAb+ tests require ongoing education and psychosocial support as they continue being monitored. Most of this will be provided in the primary care setting but it is the responsibility of all healthcare professionals involved in the monitoring and care of individuals with any stage of T1D.19,20

Education should:

- Be provided at the point of a positive autoantibody screening; at diagnosis of each stage; annually for review and maintenance; and during life transitions

- Accompany the implementation of all monitoring plans; this includes home glucose testing and any monitoring devices

- Be culturally, linguistically, and socioeconomically congruent

Topics and intensity should be based on T1D stage and risk of progression and include the risks and benefits of intervention therapies. It should also be accessible, engaging, and person-centered; it should also consider the developmental, social, emotional, cultural, and linguistic needs of the individual and/or their family.

Psychosocial Support

Clinicians should assess the emotional, cognitive, and behavioral functioning in people at risk of or with early-stage T1D and their family members, including anxiety, risk perception, and behavior changes. This includes:

- Ask the at-risk individual and/or their families/caregivers how they feel once they’ve received the news about their test results. Use guiding questions and standardized and validated questionnaires.

- Inquire about their current needs, particularly coping, at each monitoring visit.

- Integrate psychological care into routine medical visits delivered, if possible, by providers with diabetes-specific training.

References

- Insel RA, Dunne JL, Atkinson MA, et al. Staging presymptomatic type 1 diabetes: a scientific statement of JDRF, the Endocrine Society, and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:1964-1974.

- Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Teplizumab approval for type 1 diabetes in the USA. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11:76-77.

- Simmons KM, Sims EK. Screening and prevention of type 1 diabetes: where are we? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;108:3067-3079.

- Alonso GT, Coakley A, Pyle L, et al. Diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes in Colorado children, 2010–2017. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:117-121.

- Sims EK, Besser REJ, Dayan C, et al. Screening for type 1 diabetes in the general population: a status report and perspective. Diabetes. 2022;71:610-623.

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes-2025. Diabetes Care. 2025;48(suppl 1):S27-s49.

- Besser REJ, Bell KJ, Couper JJ, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2022: stages of type 1 diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2022;23:1175-1187.

- TrialNet. Pathway to Prevention screening www.trialnet.org/our-research/risk-screening.

- ASK. https://www.askhealth.org

- PLEDGE Pediatric Screening Study. https://research.sanfordhealth.org/fields-of-research/diabetes/pledge

- CASCADE Research Study. https://cascadekids.org

- Ask the Experts for Early T1D Answers and Guidance. https://www.asktheexperts.org/for-providers

- Breakthrough T1D. Type 1 diabetes early detection. https://www.breakthrought1d.org/early-detection

- Ziegler AG, Kick K, Bonifacio E, et al. Yield of a public health screening of Children for islet autoantibodies in Bavaria, Germany. JAMA. 2013;309:2473-2479.

- Swamy A, Town M, Polonsky WH. Barriers to screening in type 1 diabetes. https://childrenwithdiabetes.com/featured/barriers-to-screening-in-type-1-diabetes/

- O’Donnell HK, Rasmussen CG, Dong F, et al. Anxiety and risk perception in parents of children identified by population screening as high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(12): 2155-2161.

- Ospelt E, Hardison H, Rioles N, et al. Understanding providers’ readiness and attitudes toward autoantibody screening: a mixed-methods study. Clin Diabetes. 2024;42:17-26.

- T1 Diabetes TrialNet. TrialNet recommendations for clinicians. www.trialnet.org/healthcare-providers

- Phillip M, Achenbach P, Addala A, et al. Consensus guidance for monitoring individuals with islet autoantibody-positive pre-stage 3 type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2024;67(9):1731-1759.

- Haller MJ, et al. ISPAD clinical practice consensus guidelines 2024: screening, staging, and strategies to preserve beta cell function in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Horm Res Paediatr. 2024;97:529-545